“This is the way the world ends”

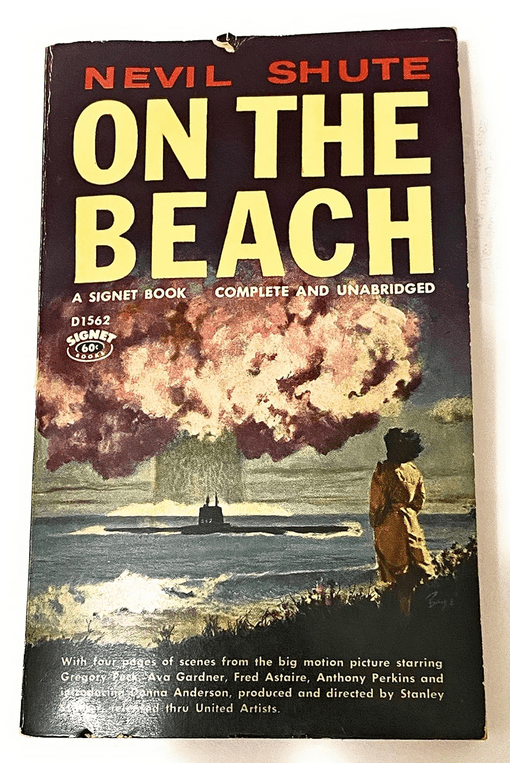

British author Nevile Shute’s classic novel “On the Beach” was published in 1957, the year in which the UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was launched, both reflecting the growing public alarm over the risk of a Third World War likely to involve atomic bombs, as the Cold War came to a head. Having emigrated to Australia, Shute set the novel largely around Melbourne on the far southern coast.

In the opening pages, we may wonder why naval officer Peter Holmes has been unemployed for months, can no longer drive his prized Morris Minor and uses a bicycle with a trailer of his own design to collect milk from a local farm. It soon becomes apparent that during a violent and ill-judged chain reaction in the previous year of 1962, so many countries north of the Equator launched nuclear “cobalt” bombs that virtually no one can have survived in the entire northern hemisphere. Now there is evidence that massive quantities of deadly radioactive dust are being carried inexorably southwards by the winds – it is only a matter of time before they reach the Melbourne area.

Shute’s style is plain and direct, even plodding, with a focus on minute detail, perhaps a product of his training as an engineer. All of this can combine to create quite a banal effect. However, although perhaps not intentionally, this adds to the sense of people subjected to a threat which often seems unreal and hard to believe.

The novel is essentially about how people react to this type of situation. Peter’s wife Mary lives in a domestic bubble, ever more preoccupied with planning and replanting her garden even when told that everyone in the area has only as a matter of weeks to live. From the outset, her feisty friend Moira seeks refuge in parties and alcohol. Moira’s father continues to spread muck on his farm to make the grass grow evenly and labours to construct a new fence on his land. Peter’s American boss Dwight speaks of his wife and children back home as if they are still alive, buying them presents. Overall, most people seem remarkably passive, perhaps because fatalistic. One could of course argue that to carry on regardless is the best course if there is no alternative. It is only when they actually see others falling ill and dying that some opt to risk their lives in the dangerous sport of motor racing, and the system of law and order finally crumbles

This potentially powerful theme is weakened by being somewhat repetitive, with the lengthy descriptions of the submarine Scorpion travelling thousands of miles under Dwight’s command, tasked with reporting on the scale of visible damage, together with any evidence of human life. Owing to the fear of contamination, only coastal settlements can be viewed through a periscope from a “safe” distance, with shouted messages through a megaphone the sole means of attempted communication.

The sometimes corny dialogue and dated attitudes may be an accurate reflection of life at the time, and inaccuracies over the nature of a nuclear calamity on such a scale are excusable. We may find it implausible that, for months, life in and around the small town of Falmouth seems to carry on much as usual despite a lack of petrol – a shortage of socks being one of the first signs of economic collapse to cause concern. Yet we need to remember the problems of obtaining information and maintaining communications only a few decades before the largescale development of the internet and mobile phone.

Also, perhaps Nevile Shute’s main concern was to shake readers out of their complacency in ignoring the writing on the wall before it was too late. “On the Beach” has renewed relevance now, when increased instability in the Middle East, and Ukraine and growing tensions between superpowers feed fears of a Third World War and spark concerns over a nuclear calamity.

Despite moments of humour, I found this a depressing read, since from the outset the outcome seems inescapable. It lacks the quality of writing and insights of, for instance, “The Plague” (La peste) by Camus to which I could relate strongly during Covid, but of course involves a less apocalyptic situation, and concludes on a slightly more hopeful and positive note.

It’s worth knowing that the book’s title was a Royal Navy term to mean “retirement from service”. It also appears in T.S.Eliot’s poem, “The Hollow Men” which includes the lines:

“In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river. This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper”.