Marietta has grown up in dead-end small-town Kentucky where her single mother makes ends meet as a cleaner. Determined to avoid the fate of her classmates who tend to fall pregnant soon after leaving school, if not before, she gains employment as a hospital lab assisant, and saves enough money to buy an old banger with a view to travelling west, although with no clear aim in mind.

In all this, her confidence and resilience may owe a good deal to her mother’s unconditional love and uncritical encouragement. So it is ironical that almost immediately, motherhood is foisted upon her when, stopping off near the Cherokee Nation reservation in Oklahoma, which her “full-blooded” Indian great-grandfather had avoided being marched into, she is too tired and decent to resist taking on the care of a small girl, thrust into her car.

This is not a “spoiler”, since it occurs in the opening chapter of the mainly quite fast-paced tale. Recounted in the first person, apart from one chapter, by “Taylor” as Marietta has decided to rename herself, this shows how she manages to survive and build relationships with a diverse range of people, including the child, nicknamed Turtle.

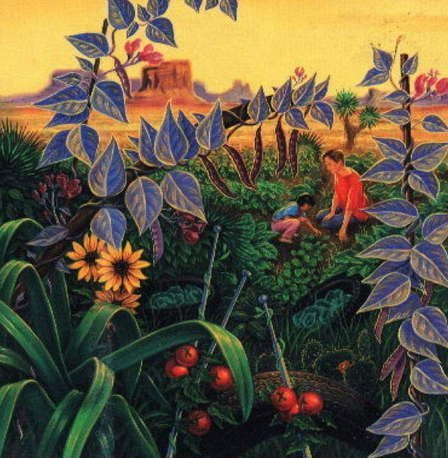

The novel avoids being overly sentimental or schmaltzy, through Taylor’s dry wit and entertaining turn of phrase, with perceptive observation of the varied people she meets. The dialogues are convincing, conveying their different personalities. There is a vivid sense of place, with the focus on the natural environment, in particular plants, which is the theme running through Barbara Kingsolver’s fiction. I have read most of it, starting with “The Poisonwood Bible” and inadvertently including “Pigs in Heaven”, the sequel to “The Bean Trees” which one should really read first.

“The Bean Trees” is her debut novel, written in the 1980s, and fascinating in portraying both the evidence of climate change, and the harsh treatment of refugees, albeit on a smaller scale than the present (January 2026), but making the reading of the book seem very relevant. Having visited the States a few times, I could relate to the descriptions, also learning quite a lot in the process. For instance, the bean trees of the novel are the wisteria, which turns out to be a form of “legume” and grows rampant over my garage wall in England.

Possibly because she describes it as being partly autobiographical, but also through being her first novel, it has the authentic freshness and vitality of writing for the sheer pleasure and urge to do so, without any expectation of success, nor the burden of a literary reputation to maintain. I like the tight, if finally perhaps contrived, structure of it, and the relative brevity of about 230 pages, leaving one wanting more, in contrast to the sometime rambling and excessive length of her later novels.

I agree with the reviewer who felt that the final plot twist is somewhat implausible, while being necessary to achieve the desired ending, but most novels have a few flaws and I recommend it, to read individually, on different levels, or for a book group, as a basis for a wide-ranging discussion.