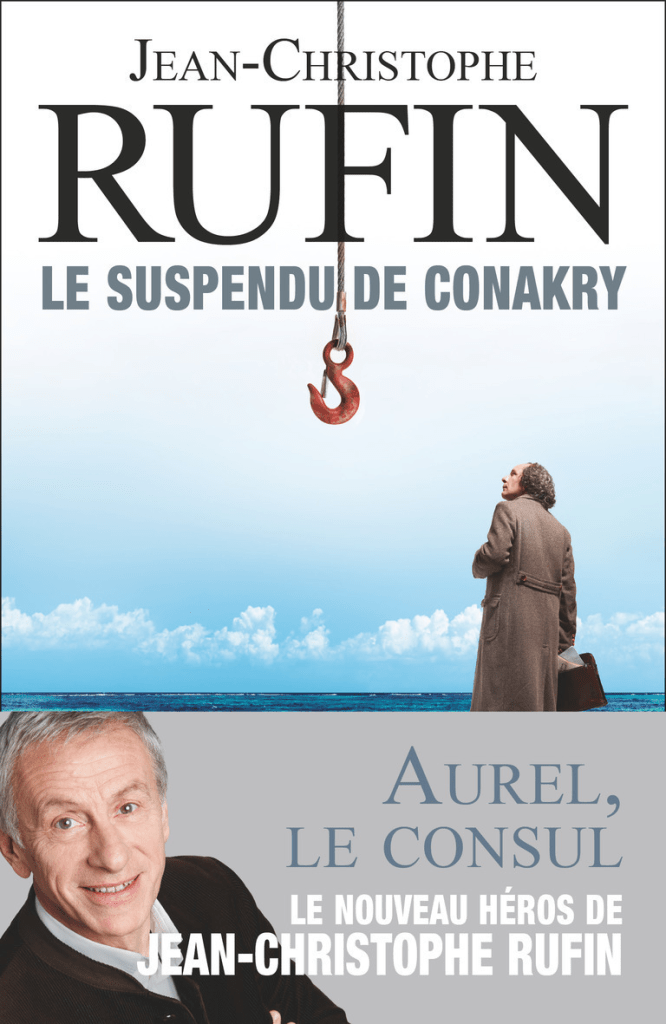

The quay of Conakry harbour is crowded with Guineans, mesmerised by the spectacle of a body suspended from the mast of a sailing boat in an apparent vicious act of revenge, but for what reason? The victim is a wealthy Frenchman who may have had a large amount of money stashed on board after selling his business, so was theft the main motive? Bored in his job, with secret dreams of being a detective, the unlikely consul at the local French embassy, Aurel Timescu, cannot resist the unexpected opportunity to investigate the crime unofficially in his manager’s convenient absence.

The first in a series which has proved popular, this novel marks a change in direction for author Jean-Christophe Rufin. With an impressive career path as a doctor playing a leading role in Médecins Sans Frontières, and as a diplomat, his past novels have been located in a variety of countries, but tend to focus on serious themes and moral issues. In some ways, “Le suspendu de Conakry” follows this pattern, with its references to the corruption and lack of freedom in formerly communist Romania, Aurel’s country of origin, to the problems of post-colonial Guinea and the insidious network of the international drug trade.

However, as detective fiction it seems quite formulaic: divorced anti-hero with a drink problem, on bad terms with his boss. Habitually wearing an ankle-length mac in a country with an average temperature of over 80° F, Aurel is widely mocked and underestimated. Yet he somehow manages to establish a rapport with hints of possible romance with Jocelyne, the murder victim’s glamorous sister. This is despite behaving like a gauche adolescent in her company. Although Rufin has claimed when interviewed that Aurel is based on embassy staff he has met, he seems to have carried absurdity too far.

The plot is rather thin and banal, with Aurel largely relying on information he deploys young local men, like Hassan who works for the embassy, to glean by quizzing possible witnesses and suspects. There is a potentially interesting twist in Aurel’s persistent attempt to understand the psychology of Jacques Mayères. Influenced by his Romanian culture which fosters a belief in ghosts, he even imagines that Jacques is looking at him from a photograph. This apparently assists Aurel to work out how the crime occurred but the eventual denouement seems implausible and contrived in too many respects. For the most part slow-paced, the novel concludes abruptly, still dangling a few loose ends.

This proves an easy read which leaves one feeling dissatisfied, because some promising ingredients could have been handled better.